The voluntary carbon market: a comprehensive guide

In its recent report, the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance argued that carbon markets will have a key supporting role in ensuring that international climate finance targets are met. The market helps in mobilizing resources (particularly vast sums of private finance) and encouraging climate action beyond regulatory requirements, providing vital funding for climate mitigation projects and promoting sustainable development.

However, the VCM has faced concerns regarding the integrity of carbon credits and the accuracy of claims about the actual amount of carbon emissions reduced. There is currently very little formal regulatory oversight governing carbon transactions, with the market relying on independent standards, third-party verification, transparency initiatives such as the Core Carbon Principles and Verified Carbon Standard, and registries that track the issuance, transfer, and retirement of carbon credits.

Despite these efforts, questions about the effectiveness and quality of some carbon credits persist, and it remains difficult to gain transparent access to the highly complex information required to assure the quality of credits being traded. However, as the VCM continues to grow rapidly in scale, new solutions are emerging to improve the credibility of the marketplace and unlock its full potential as a tool in our fight against climate change.

In the guide below, we provide a comprehensive overview to some of the most frequently asked questions regarding the voluntary carbon market.

What is the voluntary carbon market?

The voluntary carbon market (VCM) is a market-based mechanism that allows individuals, organizations, and companies to voluntarily purchase tradeable units called carbon credits to ‘offset’ their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The VCM is largely driven by non-state actors, who buy these carbon credits to compensate for their residual emissions and meet their net zero and other climate change targets. Companies usually participate in VCMs individually, but occasionally they do so as part of industry-wide schemes.

One such example is the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). International airline companies participating in CORSIA have pledged to offset all of the GHG emissions they produce above the 2019 levels set as a baseline.

How big is the market currently?

The VCM is a complex and rapidly evolving market and estimates of its size now, and projected future value, often vary. However, what is clear is that the market is expanding rapidly as demand wildly outstrips supply.

Most estimates place the current value of the VCM at $2bn - almost quadruple its value in 2020. This remarkable growth has been driven by a number of factors:

The strength of demand for carbon credits as a result of interest from large corporations seeking to meet their net-zero ambitions.

A constrained supply of carbon credits, particularly those of verifiably high quality.

The emergence of coordinated international efforts to standardize the VCM, led by the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), to increase quality and transparency in the market for buyers.

Forecasts for the future value of the marketplace are bullish, with joint research from the Boston Consulting Group and Shell predicting that the VCM will be worth between $10bn-$40bn by 2030, transacting 0.5bn-1.5bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) compared with the current volume of 500m tonnes. The Taskforce for Scaling the Voluntary Carbon Market goes even further, estimating that demand for carbon credits could increase by a factor of 15 or more by 2030, with a total market value upwards of $50bn by 2030.

What are compliance markets and how are they different?

As the name implies, participation in the VCM takes place on a voluntary basis, with companies purchasing carbon credits to meet their own climate pledges rather than government-mandated targets.

By contrast, compliance markets for trading carbon credits are established under regulatory frameworks that require entities to limit their GHG emissions or meet specific emissions reduction goals. Political entities including the EU, the UK, and the state of California have mandatory carbon markets covering specific industry sectors and gasses.

For example, California’s multi-sectoral emissions trading system covers around 450 businesses that are collectively responsible for roughly 85% of the state’s total carbon emissions, including large industrial plants, large electricity power plants, and fossil fuel distributors.

The major compliance markets operate according to a principle known as ‘cap and trade’. Under this system, regulators set a cap on the total amount of GHG emissions that can be emitted by companies required to participate in the compliance market. The cap is subsequently reduced over time so that total emissions fall.

Under the cap and trade system, companies that emit greenhouse gasses are required to hold a permit or allowance for each tonne of CO2e they emit. These permits can be bought, sold, and traded on a market, allowing companies to trade allowances with each other to meet their emissions targets. If a company exceeds its emissions target, it can purchase additional allowances from other companies that have a surplus.

The price of carbon allowances is determined by supply and demand, with the overall cap ensuring that there is a finite number of allowances available. As the cap is gradually lowered over time, there should be a corresponding increase in the price of these tradable allowances on the compliance market. This pricing signal incentivizes operators to reduce their emissions while promoting investment in innovative low-carbon technologies. The flexibility provided by the market-based trading mechanism also allows companies to cut emissions where it will cost them the least to do so.

What are carbon credits?

Carbon credits are tradeable tokens that represent the avoidance or removal of GHG emissions from earth’s atmosphere. They are measured in metric tonnes of carbon dioxide or an equivalent alternative greenhouse gas (CO2e). These credits are created by carbon projects, where the project owner conducts activities that reduce or capture carbon emissions and fund this work through the sale of carbon credits equivalent in volume to the project’s impact.

Avoidance

Credits representing tonnes of CO2e avoided are created by projects that prevent GHG emissions that would have happened otherwise. This can be achieved by several means, for example through projects that:

Replace fossil fuel power plans with renewable energy farms;

Increase industrial energy efficiency,

Improve waste management processes to reduce methane emissions;

Prevent deforestation that would have occurred otherwise.

These projects reduce the flow of emissions into the atmosphere by comparison with a hypothetical baseline in which more carbon intensive alternatives would have taken place instead (i.e. burning more fossil fuels or cutting down more trees).

Removals

A removals credit is, unsurprisingly, representative of 1 tonne of CO2e that has been removed from the atmosphere. Carbon sequestration is typically done via nature-based solutions such afforestation (creating a new forest where there previously was none) and reforestation (replanting trees to replace those cut down in an existing forest) projects, or by using direct carbon capture technology that sucks CO2 from the air and stores it deep geological formations.

Many of the carbon projects that create these credits also contribute additional social and environmental ‘co-benefits’ as a result of their work, providing income to local communities, conserving nature and protecting biodiversity, improving local health, and other positive outcomes.

Owners of carbon credits acquired through the voluntary markets can decide what to do with them. Typically, entities purchasing carbon credits do so with the intention of retiring them on an offset register. This means that credit can never be sold on to another buyer and the final owner has an exclusive claim to have ‘offset’ (i.e. compensated for) the CO2e they have emitted.

For instance, corporate buyers will purchase a certain volume of carbon credits to offset a portion of the emissions they generate in line with their net-zero transition pledges.

Alternatively, owners can trade their credits to an end buyer through a carbon exchange platform. In this way, supply and demand for carbon credits are linked by retail traders as in other commodity markets.

As carbon credits are tradeable units, one of their great benefits is that they allow for funding to flow towards carbon project activities that are most effective at reducing emissions anywhere in the world.

What types of project create carbon credits?

There are a range of different types of carbon projects that are effective at avoiding and removing GHG emissions.

Nature-based solutions

Nature-based solutions (also often referred to as natural carbon solutions) remove and reduce emissions by enhancing the ability of natural ecosystems to sequester CO2e or through reversing the degradation of ecosystems so that they don’t release carbon into the atmosphere.

Examples of nature-based solutions include:

Forestry and land use projects that protect, restore, and create forest areas. This includes work that falls under the RED+ framework that guides activities in the forestry sector aimed at protecting against deforestation and forest degradation, as well as the implementation of sustainable forest management practices.

Blue carbon projects that protect and restore coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, seagrasses, and tidal and salt marshes. These ecosystems are important due to their capacity to store high volumes of carbon within marine plant life and the sediment below.

Agricultural projects that improve land management practices on farmed land so that emissions are reduced and soils sequester carbon at their maximum potential.

‘Green-gray’ infrastructure projects that seek to ensure better integration of nature into urban communities and agricultural landscapes.

Other carbon projects

Other carbon projects rely on technology to avoid or reduce emissions. For example:

Renewable energy initiatives that replace fossil fuel power plants with clean energy infrastructure and decarbonize local energy grids.

Direct air capture technology that removes CO2e from the atmosphere.

Energy efficiency and fuel switching projects that reduce the energy consumed by local industry and replace fossil fuels with sustainable energy sources.

Waste management projects that improve the efficiency of waste disposal processes, for example landfill projects that capture the methane released from waste and turn it into fuel.

Nature-based solutions in particular also have an important role to play not just in reducing emissions but in helping those on the frontline of the climate emergency adapt to the impacts of climate change. For example, blue carbon projects that protect and restore marine ecosystems are effective in protecting nearby communities from flooding and coastal erosion.

How does the voluntary carbon market work?

As the VCM grows in size and complexity, the number of different stakeholders operating at each of the value chain from project creation to delivery is increasing (as this comprehensive market map illustrates).

Sustaim.earth's market map. Original image here.

In general, however, there are five main players engaged in creating and trading carbon credits.

Project developers

At the top end of the chain on the supply side are project developers, who set up the carbon projects that eventually issue carbon credits. They are responsible for:

Sourcing and/or initiating projects.

Bringing together financing and implementation partners to deliver credits.

Working with standards and verification bodies to ensure the integrity of the credits they deliver.

Working with an extensive network of distributors and traders to deliver an auditable trail of carbon offsetting claims.

Each credit delivered by developers will have a vintage that confirms when it was issued and a delivery date indicating when it will be available on the VCM.

End buyers

Representing the market downstream, the VCM is made up of end buyers (usually companies but occasionally individuals) that have committed to offsetting some or all of their GHG emissions.

Major early adopters of carbon credits came from traditionally carbon intensive industries such as natural gas and aviation, as well as major tech companies such as Apple and Google. The market continues to grow rapidly as a wider range of organizations, particularly in the financial sector, develop their own net zero strategy or look for a way to hedge against the financial risk posed by the transition to a low carbon economy.

The implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement at COP26 also created a mechanism for countries to purchase carbon credits in support of their national emissions reduction targets.

Retail traders

As in other commodity markets, supply and demand are linked by brokers and traders operating in the middle of the value chain.

Retail traders purchase credits in large volumes directly from the project developer. They then bundle credits together into portfolios and sell to end buyers for commission. While many credits are traded privately or over the counter, carbon exchanges are now emerging to simplify and accelerate the trading process. Some of the largest exchanges include Xpansiv CBL, AirCarbon Exchange (ACX) and Carbon Trade Exchange (CTX).

These exchanges create standardized products that remove some of the complexity involved in credit trading as a result of the wide range of factors that affect their pricing. These standardized bundles also ensure that some basic credit specifications are respected and that credits issued under their label are guaranteed to have set characteristics. This might include:

A specific type of underlying project, e.g. credits generated from nature-based solutions such as RED+ or blue carbon.

Certification from a specific group of standards or verification bodies.

A recent vintage.

The standardized products offered by exchanges are favored by traders and other players in the financial industry engaged in conventional commodity trading. These are investors looking to buy and hold credit portfolios in anticipation of skyrocketing demand and price increases.

End buyers looking to purchase credits to offset their emissions prefer non-standardized products as it allows for greater due diligence on the nature of the underlying projects that create the credit. This makes it easier to protect their brand from accusations of corporate greenwashing by individually verifying the integrity of the credits they are purchasing.

Brokers

Like retail traders, brokers link supply and demand by helping the end buyer to navigate through this highly complex marketplace. They take an active role in working with end buyers to identify and purchase credits, which are often sourced from both retail traders and directly from project developers.

They can also play a useful role in helping developers, who often lack marketing expertise, to connect to buyers and make their project financially viable.

Standards bodies and ratings platforms

Unique to carbon markets, these are organizations that set quality standards frameworks and verify that a particular carbon project meets its stated objectives and has removed/avoided the stated volume of CO2e.

These standards bodies develop methodologies for assessing the value and integrity of different types of carbon projects. Calculating the amount of CO2 absorbed by a reforestation project is a highly complex process requiring its own unique methodology distinct from that of assessing the impact of a renewable energy project.

However, there are certain core principles that certifications seek to verify regardless of the nature of any given project:

Additionality: The CO2e reductions achieved by the project should be ‘additional’ to what would have happened in a business-as-usual scenario. The project should therefore not cover activities that are legally mandated, existing common practice, or otherwise financially attractive in the absence of revenue from carbon credit sales.

Permanence: The outcome of the project should be a permanent reduction in the CO2e emissions that have been avoided or removed from the atmosphere. These reductions should not be at risk of reversal - e.g. a forestry project might be at risk of reversal due to wildfires, and this should be accounted for in the project development phase.

No overestimation: The carbon credits issued should accurately reflect the volume of emissions reduced by project activities, also taking into account any unintended GHG emissions caused by the project.

Exclusive claim: Each metric tonne of CO2e represented by a carbon credit must only be claimed for use as an offset once.

Projects are also expected to comply with all the legal requirements of the jurisdiction in which it is based.

The major standards-setting organizations include Verra, Gold Standard, and the International Carbon Register. Ratings platforms, which provide carbon credit analysis and quality assurance for buyers, include Sylvera, BeZero Carbon.

How are carbon credits priced?

Carbon credit prices are determined by a complex interplay between a number of factors. In addition the the usual rhythms of supply and demand that dictate commodity pricing, projects that possess certain qualities command a premium among end buyers:

Carbon removal projects create credits that trade at a higher price compared to avoidance credits because they require higher levels of initial financing and are more attractive to buyers who perceive them as a more effective tool in mitigating climate change.

Projects with a more recent vintage trade tend to be valued more highly.

Projects that generate more co-benefits for nature, biodiversity, and local communities are more attractive to buyers. This means that credits generated by nature-based solutions are in higher demand due to their valuable work in nature restoration and conservation.

The lack of access to transparent information in the marketplace means that additional variables have an uneven impact on credit pricing. For example, the underlying projects that generate credits vary considerably in their actual environmental performance, but this variation is only sometimes reflected in credit pricing as this information is not always visible to end buyers.

It is for this that we have seen the emergence of carbon intelligence and ratings platforms that aim to help buyers assess the true environmental value of the credits they are purchasing to offset their emissions.

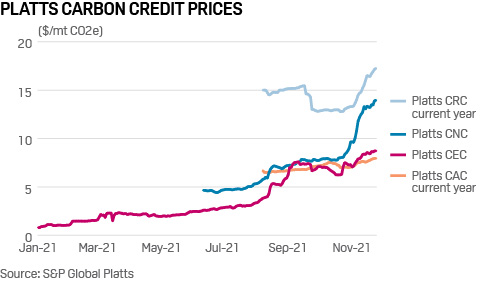

There was astonishing growth in the price of carbon credits over the course of 2021.

How are carbon projects funded?

While carbon projects are ultimately funded by the revenue generated from sales of carbon credits, these projects require substantial upfront investment and intermediate financing to start their work.

To scale carbon projects in order to meet the skyrocketing demand for credits from corporate buyers, more developers are actively seeking finance for their project pipelines. Historically, the carbon finance model has relied on project developers using small-scale equity investments, conservation grants, and development finance to fund the early stages of project design, feasibility assessment, and implementation.

Once a project was verified, it could be marketed to the few corporate buyers investing their corporate social responsibility budget into credits for use offsetting their emissions.

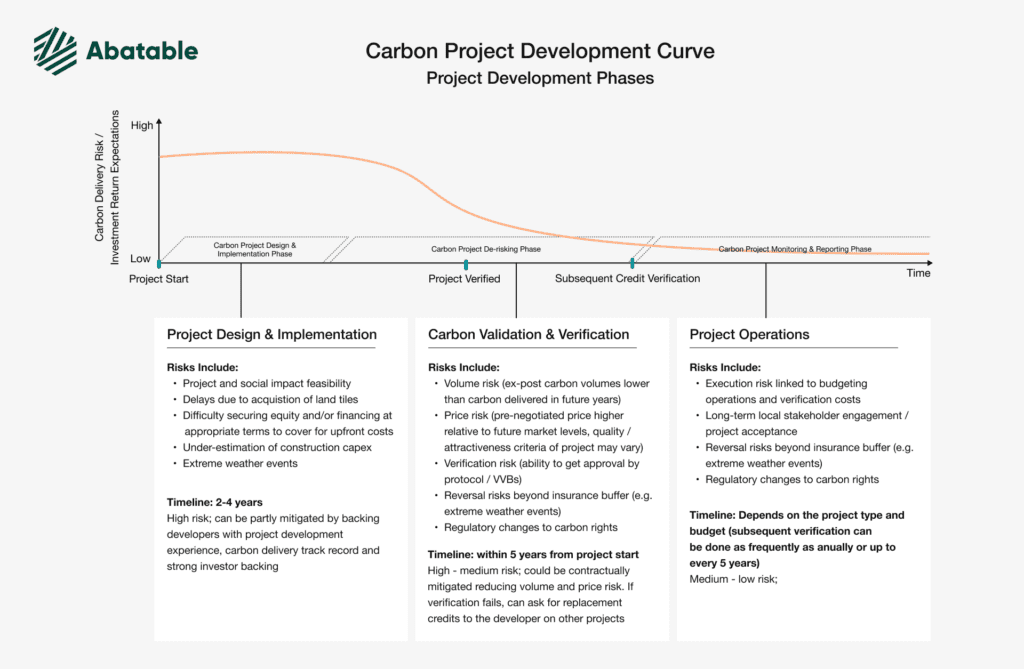

As the rise of corporate net zero initiatives has increased demand for credits and driven bullish growth projections for carbon markets, new financial players are taking an interest in the VCM and additional investment streams are opening up to developers. Analysis from the carbon intelligence and procurement platform Abatable describes this changing landscape in their blog on the carbon project development curve:

‘Carbon streaming and investment funds, as well as financial intermediaries and some carbon trading desks have started to offer structured finance solutions to developers, investing capital and taking a higher level of risk, often in the form of project verification and implementation risk. These structured solutions facilitate developers who now can use less equity at later stages of development and allows developers to unlock capital which can be re-invested to finance earlier stage pipeline development.’

Abatable - a carbon intelligence and procurement platform - has mapped the carbon project development curve. Full article here.

Though it is getting easier for developers to secure financing for their project pipelines, the perceived lack of transparency involved in carbon credit transactions, and an insufficient understanding of how carbon financing works, continues to keep potential investors at bay. Furthermore, the inherent complexity of developing a new carbon project and accurately valuing a project makes it even more challenging to build trust with investors.

As momentum grows behind the VCM and developers seek to scale the supply of credits accordingly, innovative new technologies and solutions are emerging to help increase transparency and enable robust de-risking processes early in the design and implementation cycle.

For example, data collectors and processes are using machine learning and remote sensing technologies to improve the measurement and modeling of carbon quantities sequestered in forestry projects. They are also developing sophisticated methodologies for accurately measuring the exposure of forestry carbon projects to physical climate risks such as wildfire - a process that is essential in ensuring that emissions are permanently reduced and not at risk of reversal.

To read more about how carbon project developers are de-risking their projects for potential investors, read our case study here.

Who regulates the voluntary carbon market?

There is no single, overarching authority that regulates the VCM. The rapid development of carbon markets and the voluntary nature of most participation in its related activities have led to the emergence of a global patchwork of standards and regulations.

In lieu of standardized regulations at the policy level, the VCM instead relies on a combination of international standards frameworks, independent third-party verification, and market-based quality assurance mechanisms.

International standards and frameworks

A number of independent standards have been developed to ensure the quality and integrity of carbon credits in the voluntary market. Some of the most widely used standards include the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), Gold Standard, American Carbon Registry (ACR), and Climate Action Reserve (CAR). These standards provide guidelines for project development, monitoring, reporting, and verification of emission reductions.

Standards in the voluntary markets are significantly impacted by the organizations involved in these markets. For instance, the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), an autonomous governing entity, conducted lengthy consultations on Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) and an Assessment Framework (AF), and an update on these new draft standards is expected in Q1-2 2023.

Third-party verification

Independent auditors, known as Designated Operational Entities (DOEs) or validation/verification bodies (VVBs), assess projects to ensure they meet the criteria established by the selected standard. These entities verify the project's emission reductions and validate its additionality, ensuring that the project would not have occurred without the financial support from the sale of carbon credits.

Carbon registries

Carbon credit registries play a crucial role in tracking the issuance, transfer, and retirement of carbon credits. They help to create an auditable credit trail from project implementation to credit purchase that provides transparency and prevents double counting of emission reductions. Some registries are linked to specific standards (such as Verra, which developed and runs the VCS), while others are independent platforms that support multiple standards.

Industry associations and NGOs

Organizations such as the International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance (ICROA), the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, and the Verified Carbon Standard Association (Verra) promote best practices and work to improve the transparency, credibility, and overall functioning of the VCM.

Looking ahead, it seems inevitable that formal regulation of the VCM will increase in line with climate-related legislation that will also lead to further growth in demand for carbon credits. There isn’t yet a single, globally accepted, consistent methodology for defining and calculating carbon assets and liabilities.

Recent controversies have raised questions about the integrity of carbon transactions - how emissions reductions are calculated and validated, how the existence and legitimacy of a carbon project is verified, how retired credits are counted etc. These kinds of assurances require complex information and participants in the VCM are engaging more actively in due diligence to protect themselves from reputational damage. The formal adoption of the voluntary frameworks described above into national and international regulation could help to resolve ambiguities and reduce opportunities for inaccuracies and fraud.

At Sust Global, we’ve developed a proposition for offset quality assessment and permanence potential analysis for nature-based solutions and nature-based regenerative finance projects.

We are currently partnering with teams on carbon project financing, nature-based carbon project development and offset ratings, helping on the measurement, mitigation and management of blue carbon, soil carbon, and forest carbon projects. You can learn more about our product here.

If you would like to chat with us about how we can support your work in the natural carbon sector, fill out the form below and a member of the team will be in touch.